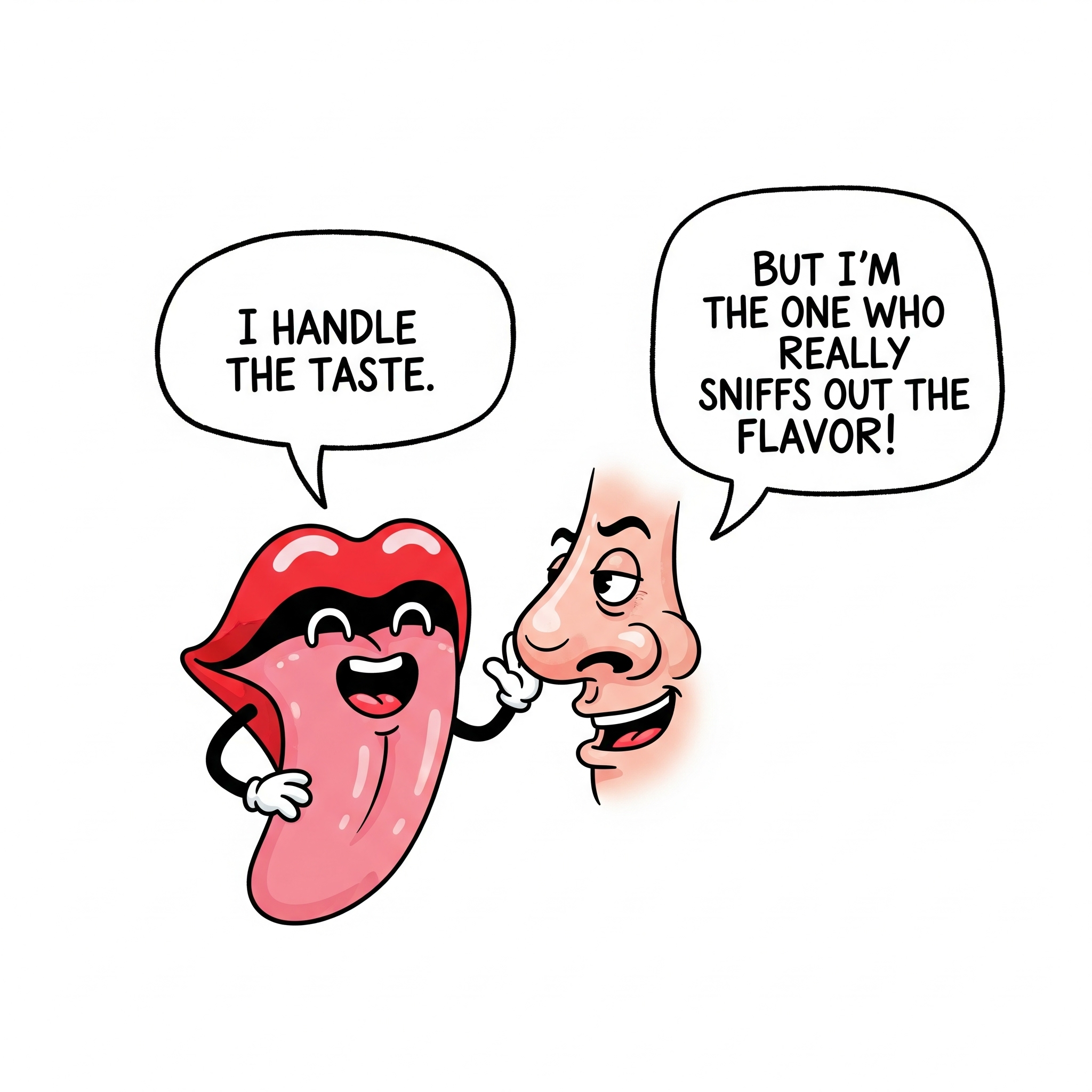

Have you ever noticed how bland food tastes when you have a cold? You might assume it’s just your taste buds acting up — but the real culprit is your nose. Surprisingly, your sense of smell plays a much bigger role in tasting food than most people realize.

Taste vs. Flavor — What’s the Difference?

Let’s break it down. Your tongue can detect only five basic tastes:

- Sweet

- Salty

- Sour

- Bitter

- Umami (savory)

That’s it. So how do we perceive the rich, complex flavors of foods like chocolate, curry, or fresh strawberries?

That magic happens thanks to your sense of smell. Flavor is actually a fusion of taste, smell, texture, and temperature. And smell alone accounts for up to 80% of what we consider flavor.

How Smell Enhances Flavor

When you eat, aromatic molecules from your food travel through:

- Your nose if you smell the food before eating (called orthonasal olfaction).

- The back of your throat to your nose as you chew (called retronasal olfaction).

These scent molecules stimulate receptors in your olfactory system, which works together with your taste buds to build the full flavor experience. It’s a complex neural symphony — and your brain conducts it beautifully.

Why Food Tastes Dull When You’re Sick

If you’ve ever had a stuffy nose, you’ve experienced the loss of retronasal smell. Without scent molecules reaching your olfactory receptors:

- You still sense sweetness or saltiness…

- …but the depth and richness of flavor disappears.

Chocolate might taste merely sweet, and coffee just bitter — but the warmth, aroma, and nuance are gone. That’s your nose taking a break — and taking your flavor with it.

Try This at Home: The Jellybean Test

Want proof? Try this simple experiment:

- Pinch your nose shut and pop a jellybean in your mouth.

- Chew — you’ll notice a generic sweetness, but no flavor.

- Now release your nose mid-chew — boom! The full flavor suddenly appears.

That’s your retronasal smell in action.

The Unsung Hero of Eating

Every bite of food is a multisensory experience, and your sense of smell is the silent hero that brings it to life. Whether it’s the warm spices in a curry or the zing of citrus in a dessert, it’s your nose that unlocks the story behind the flavor.

So the next time you enjoy a delicious meal, take a moment to breathe it in — literally. Your taste buds will thank you.

Why then is it that western cuisine advocates drinking wine or liquor or low alcohol drinks with food? This is presumably done to ‘cleanse the palate’ after every bite so that epicurean sensation is reinvigorated. Is it possible that taste and smell have a bidirectional (re. cause-effect) relationship?

Wine is drunk with food for a couple of reasons

1) Cleanse the palate:-Wine’s acidity, tannins, and alcohol cut through fats, proteins, and oils, resetting the sensory baseline so the next bite feels as vivid as the first which counteracts sensory adaptation, where taste receptors become less sensitive to a stimulus over time.

2) Enhance flavor:- Acidity in white wine can highlight the umami or sweetness in food, bitterness in tannic red wine can soften salty or protein-rich dishes and alcohol can solubilize fat-soluble aroma molecules, enhancing retronasal olfaction.

With that being said, yes, there is a bi-directional relationship between smell and taste which is both neurological and psychological

1) Neurological Integration:- The brain merges taste and smell into a unified percept called “flavor.” Smell influences how we perceive taste (e.g., vanilla makes things seem sweeter), and vice versa — for example, a sour taste can sharpen the perception of citrusy or vinegary aromas.

2) Expectation and modulation:- The brain modulates olfactory and gustatory inputs based on context, memory, and expectation. So, for example, if you expect a lemon to be sour, your brain may prime your taste buds to anticipate sourness — even if it’s a sweet Meyer lemon.

3) Cross-modal perception:- Smell and taste can influence one another dynamically so that a food with complex aromas may change how you perceive its sweetness or bitterness.

So yes — smell and taste have a bidirectional relationship, and wine culture exemplifies how humans have learned to use that interplay for deeper pleasure.